Description

About This Video

Transcript

Read Full Transcript

Hi, Jennifer Golden, zoom in here and just thrilled to be back at Peloton anytime. Uh, today I want to share with you something that has been really intriguing me lately, which is the effect of tissue adhesions on movement. As politesse instructors, there's a number of different skills that we start to develop. We certainly learn our repertoire and then we learn our anatomy. We get our academic mind going, we develop our eyes to be able to see what's happening in the body. We develop our hands depending on your approach to see what we feel. Um, but there's another component, which is our perspective and thinking about the way that tissue moves in the body might be a different perspective on the way we look at movement, the way we see muscles engaging or stretching.

So what we're going to do today is I have a couple goals that I'd like to convey during this tutorial. First, I would like to think about investigating and exploring the role of adhesion. Oh, I'd also like to talk about what adhesion means. Like sometimes it's scar tissue, sometimes it's the effect of inflammation or infection. Sometimes it's just the results of immobilization and area that we don't move a lot. I would also like to think about the quality of movement and the idea that the way we approached the movement, the quality and the perspective we're taking on movement may even be more important than the choice of the exercise itself.

I would like to invite you to look at this tutorial as a stepping stone for a new way or a different way or an alternative way to look at the body and to look at movement. Certainly this is a short tutorial, so we're not going to do an extensive anatomy lesson, but it should be an inspiration. And I'd like to inspire you to be a little curious about some of the mysteries that the body holds. So let's first think about, um, what is the anatomy of our fashional tissues are our skin, our fascia layers. We've got collagenous fibers and those collagenous fibers provide a lot of the structure. We've also got the Elastin, which provides some of the flexibility and the resilience. And those are within a ground substance matrix that creates a viscous systems. So we've got collagenous fibers, maybe rope ear, and the, the solution that they're in can be stickier or it can be more slippery.

We're looking for in healthy movement and healthy tissue, we've got a lot of glide between tissue layers. They're slippery, they slip around each other and then there's enough integrity to the Collagen into the matrix that it still maintains some structure and a sense of resilience. So you stretch something, it responds and it can react to forces and it can be protective. Now when tissue becomes damaged. So that could be from a surgery, that could be from an infection. We get a disorganization of that matrix. So an example of that would be a surgery.

So imagine that someone has a surgery and let's give an example of an appendectomy surgery. So imagine someone has, uh, an appendix surgery and then there's an incision. Every time we have an incision there and that heals, you end up with a seam where there was not a seam before. So what you have now is a new adhesion, a new relationship, a new connection between areas that did not have a connection previously. So that will affect how those tissues glide. So if you have a seam somewhere now and give an example of our abdominals when we breathe and when we move that our layers of abdominal muscle and fascia would glide upon each other and then now you've got this new seam.

So there's an area there that will stick and that will not glide and will not glide the same way again. Uh, there's, I think it's something like only 70 to 80% of a, of the scar is only 70 to 80% as strong as the tissue was prior to that damage. Whenever we have this sort of adhesion in the tissues, we end up with a lack of glide. And with that lack of glide, we can get a rope, enos or a tethering two different structures in the body. So back to that example of the appendectomy, not only does the skin, which might actually start to look quite healed, you could see almost no scarring left from that surgery. And the surgery honestly could have been 20 years ago or longer.

But beneath the surface, what we don't see is the adhesions that are happening between layers of Fascia and between the viscera or the Fascia layers to the visceral. So we've got depth of layers here. We've got our viscera or organs inside a bag, which is called that peritoneum. The peritoneal bag has layers of fascia around that and then come our layers of Fascia that have the muscles that we would know, our transverse abdominis, our internal obliques. So when we've cut through that, those fibers begin to adhere together. And even in the viscera we might get adhesions between each other and some of the other structures that are within the Oregon bag or inside our parents to IOM. When those structures form adhesions or begin to tether, um, or become more fibrous cause those, the Collagen, when it comes into heel, it's the same stuff you had the healthy stuff, your collagen comes into heal.

It's going to come in along the lines of strain and stress that are formed by the damage, which could be from the infection, from the appendix in the first place, and can also be from the surgery. So they come in and now they're organized along the line of the damage, not along the lines of movement, which is where they had the healthy tissue had previously laid it down. So what we need to do is remodel that tissue so that the viscera can begin to contract or get glued together. And over time that winding up, that sticking together that gloominess can prevent the movement of our diaphragm, prevent full breath and actually could then be the source of stubborn low back problems or stubborn hip problems type. So as there's so many things that we look at as platas instructors we see in our clients or we see in ourselves, and you might never think, oh that old appendectomy or the old Syrian or the hernia or a PZI tummy or anything like that could actually be the source of a snag or a tug that has wound things up inside.

So there's a few things that we can do with movement and the biggest part of that is actually just considering that is part of the issue. Then also there's body work that many people do to get in there and help to start to move things around and change it. And I've seen changes whether that surgery happened a few months back and it's part of the rehab process or whether it was 40 years ago. And I've seen people working on these old scars and just having that realization that, oh, this might be part of my problem, that actually starts to unfold an entire pattern of disorganization in the body that you may just have been blind to in the past. Let me give a little example of what can happen cause sometimes it's not really just at the site of the surgery.

So I made a little model right here and this was um, an example. I uh, got to attend fascist summer school at University of alm and this wonderful South African body worker and Fascia researcher, Willem Foray, he was describing scar tissue. He was specifically talking about, um, mastectomy, which I will add. I took a lot of inspiration from this. Um, and the reason I was excited to come and talk about this right now is because you're seeing me today, right between finishing up chemotherapy for breast cancer and I'm a few weeks away from a bilateral mastectomy. So what is a good, uh, philosophies instructor do is I dive into it academically and start studying my scar tissue. Just getting ready for what I'm going to do afterwards. So his example that he did, which blew me away was very simple. So I've got a book here and I put the colors in the book so you could see as though this is different layers of tissue. Certainly the tissue in the body is not straight across linear. It's um, they're more like a basket weaves laying upon each other in different directions.

But this example I think gives a nice visual so you can see at first as I move it around how the layers glide together because they're lined up because the fibers are laying against the line of the force. Here are line of the stress. Um, you can see that the fibers all moved together, that these lines move together. So now is an example. If there were a scar here, so I'm going to use my hand to do my best to show you. Just pretend right around here there's a scar and this is, this part's fixed. So here's where the surgery is. This part's fixed.

So what happens is you might think, okay, here's the problem, so we would need to work this out and work through here and get glide here. But what we don't realize is that as we do that you get disorganization in other regions. So if you can see here that by fixing this part, these other areas buckle and gap and they don't glide together so they can't glide like they did when this is fixed. And what this gentleman did in his research and what he discovered in this research is that even though the breast surgery scars might be in certain areas, that around the rib cage or around the left is actually where a lot of adhesion was. Now, I think that's great news for us as pilates instructors cause truly as politesse instructors, it's not really within our scope to go to go right in there and to try to work directly on a scar directly on the injury. Say it was a knee injury, anything like that. We don't really go in there and work directly on it, but we can address adhesions that occur in other areas through movement and through our queuing and our perspective on what we're trying to do. I'm going to give you an example now of a way that I might treat an abdominal abdominal surgery issue. And I've used this technique quite a few times with um, clients that had maybe old Syrians or uh, I have a lot of clients that have persistent back problems and you know, sometimes it's actually just hard to get into their core.

And then we discovered that really, I think it's the old Syrian is making it very difficult for the abdominal tissues to glide. If the muscles are too tight, they actually can't slide anymore. So I'm gonna use just a soft soft ball right here and I'm going to use this just to give a little bit of feedback. So I'm going to lay on my back here and I'm just going to rest the ball on my abdomen first and I'm doing this lightly and I'm doing it by myself. I'm not pressing down on my organs and the first thing I'm going to do is just really lightly roll around on my abdomen. Now when you do this, do it clockwise. That's important for your digestion, so just gentle and I'm starting to wake up the sensory receptors in the superficial part of the abdomen abdominals. We often try to go deep as polite as instructors, we think like we need to get the deep muscles. The truth of it, I'm going to say none of them are really very deep. They're all just around the Oregon bag. They're not really that deep.

Most of our abdominal or examinal tissue or abdominal muscle, the protein contractile factor is quite superficial. Even the deepest layer, we're only talking very different between each other right here, very, not very much difference between the different layers. So when we do this, what we're trying to do here is just sort of soften and develop some awareness and I'm going all the way around from the rib cage towards the pubic bone and then I'm going to arrest it on the abdomen and let my fingers just relax here. What we have to do to get into the layers and to start to create, uh, a therapeutic pressure interplay is to relax the breath and allow the breath to be very gentle. And that means I would like you to breathe in a way that you can't really hear and can't really see often that's best just to breathe in and out through the nose. So I'm going to stop talking for a moment and show you what I mean. And on the exhale, you want to feel that the ball can sink into the abdomen uninhibited. If we're doing our, um, what a lot of us might see as like a polities breath or Palase abs in some way.

When you exhale, you'll feel almost like a trampoline of tension. So the ball starts to drop. Or if you do this, that's just a second. I don't know if you can see that. A lot of us might go like this and that's just a second. That's just attention we want to do is relieve the tension so the layers of abdominal muscle can glide on each other and that will free up the diaphragm and free up the pelvic floor as well. So when we breathe in, it's relaxed in the diaphragm and relaxed in the pelvic floor and then the ball falls in completely uninhibited, just drops all the way down. That might take, it might take a little while, it may take a number of breaths to do that, but really give yourself the time, give yourself the time to do it.

You could pause the video right now if you want and give yourself the time to wait until that really happens until you really feel it. Release all the way down. And once you do, we're going to do the corners. This helps to release the so as, so you're going to straighten one leg and just bring it down so it falls into the cove of the ILIAC crest here. And we just do the same thing. And as you breathe in, allow almost a balloon feeling to inflate into the space between your tailbone and your pubic bone so the pelvic floor can relax on your inhalation. And then as you exhale, allow the ball to sink, sink all the way down, and you'll start to feel where you have tension.

Like I can feel for me right now. I want to move the ball just a little bit right here. I must have some tension through the obliques right here that I'm noticing. So my body is telling me, just move the ball over here. When you start to look at the idea of the tissue glide rather than the tissue muscle tension or stretch, then it'll change the way you queue and it'll change exactly what you're doing with the exercise. So if I'm thinking, um, that the muscles need to either work or need to stretch, then that will take me out of the idea that what I'm really looking for is the muscles sliding.

So when we are doing an exercise and you're using a muscle, I want you to visualize like a sponging, a sponging of the tissue. When we engage at where sponging it, where and then we're allowing it to rehydrate kind of picture like a squeegee motion. Um, and we can do that with a foam roller. We can do that. If we're massaging with the ball, whatever we might use for like a Myo fashional tool, imagine that you're not trying to like work it out, but instead you're squeegeeing through and you're pushing the fluid through and then allowing it to re saturate. And that saturation is what is going to bring the, uh, the viscous quality and what we'll call, um, this go elasticity to the tissue to allow it to be more supple, allow it to heal and allow it to have the most movement possible. If there's any scars, whenever we do these exercises, we'll want to do it in a resilient range. We don't want to go for a big stretch or a big work.

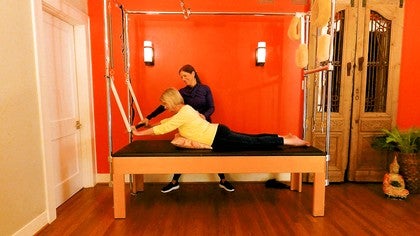

So I'm going to give another example right now. I just stretched out. I just released this side. Certainly you can do both and I would normally spend more time on that, allowing that to release. So now that I released it, I'm going to look for a little bit of a uh, resilient stretch on. So you can do this on the Cadillac table. Um, I have clients that do it on their bed or something like that. They're just going to lay, lay down and allow that whole area just to relax.

So I'm working on the same side here and I'm just breathing into the whole capsule from the pelvic floor to the diaphragm. Again, in this very gentle breathing pattern. And then once you feel nice and heavy in the hips, which will take more time than I just took, I'm going to start gently lifting yourself up and down. This may feel uneventful if you're used to a big stretch. It may not feel like it's heroic enough or powerful enough like you're like, I don't, I have a lot of clients that start this and say I don't feel anything. I don't feel anything. And the key is to maintain the gentle breath and maintain a gentle motion. And then as we do that, little by little, keeping the hips heavy and keeping much of the body relaxed, we start to get this gentle, resilient action through the tissues and that allows it to glide and to reorganize as we move.

So hopefully what I brought you today gives you some ideas. If, if I've done my job here, then what you are thinking right now is, oh, I want to try that with this exercise. Or I wonder what will happen when I do the tower and I start to move the feet and feel that sense of resilient recoil through the calves. That's my goal for you right now. My goal for you right now is to take this little morsel of information, this little idea, and to broaden that and allow that to be, become part of your, uh, entire perspective on movement in the body.

So if I have done that for you, then I have done my job and I thank you so much for watching this video and I look forward to seeing your notes and comments on how you brought this to your [inaudible] world. Thanks for watching.

Tips for Teachers: Working with Contraindications

Comments

You specifically addressed some issues I have been having in my hips from rheumatoid arthritis. I also tore a calf muscle last year and have been slowly rehabbing that with gentle stretching and foam rolling. Although a slow process, it has been coming along with these exact principles. I’m wondering if you can describe a way to do this for the lower back (my husband’s issue.)

Most importantly, I send you my best wishes for your full return to health. It takes a very special person to want to help others in their pain while you are going through such pain yourself and you do it with a wonderful positive outlook! I thank you for it. Best wishes.

I tried your abdominal - ball- and -stretch work and it felt great. I do get the gliding idea being familiar to the fascia research. How would you then apply this to a knee- surgery, or a shoulder injury?

I would love to hear more on this topic!

But most important: I wish you all the best, - all the healing-energy you need to overcome this illness! It is visible that you have the positive vibes that are so helpful in this process!

For the stretch to be more permanent though, doesn’t it need load?

If you consider what I attempted to demo with the book, we can search for areas away from the direct concern to see how adhesions may have formed elsewhere. For example with the shoulder, I would look along the chest, upper back, and lateral rib area for "sticky spots" and use a similar technique in those regions. In my experience, when they can get better glide in those regions, it is easier to then proceed to focusing on improving the mobility and organization of the joint itself.

Hope that helps inspire some exploration!

You need to be a subscriber to post a comment.

Please Log In or Create an Account to start your free trial.